Occupancy Urbanism’s Life-Worlds to frame Master Planned Lawfare

Varun Patil & Solomon Benjamin

Set to be published in City as Method: A Toolkit from Bangalore

This is an abstract of a draft chapter as of 2nd Jan 2025 that will be subsequently published in an edited volume City as Method: A Toolkit from Bangalore Edited by Smriti Srinivas and Hemangini Gupta. While we will appreciate you contacting us for further conversations and references, at this stage please do not quote without permission of the two authors Varun Patil <varunpatilbengaluru@gmail.com>, and Solly Benjamin <solly.benjamin@gmail.com>. The text here will build on that chapter to explore it’s various wider context of land regularization within South Asia, and other sites globally including in the ‘North’.

Akrama Sakrama (henceforth AS) as the Karnataka version of a seven decade experienced land regularisation is premised in popular politics that across India and global south has proved to be socially just. Being redistributive of land serviced with essential public investments, it’s with immediate and positive impacts to 85% of Indian urban territory upgrading both shelter and settings of job oriented small firm neighbourhood economy. Its counter from elites in Delhi, Mumbai drawing on ideas of master planning, now in Bangalore increasingly set in environmental terms spurred by the 2020 floods and 2024 summer drought1. Occupancy Urbanism (OU) as an analytic of territorial contestations materialized in land tenurial practices places both Akrama Sakrama and Master Planning in epimestic and ontological eqivalence. This helps theorize such contestations in immediate and material terms. OU questions assumptions shared by elite civic society, technocrats, and NGOs and many urban academic practitioners across ideological lines and portrayed in the English media: the AS reflects real estate fueled ‘corruption’ supporting the ‘land mafia’ and thus symptomatic of Master Planning (henceforth MP)’s failure to address issues of social justice or economic development and globally competitiveness. Here, the OU analytic reveals how, on the contrary, MP’s rigid zoning reinforces elite power around several self-reinforcing and intersecting political contestations de-politicizing their privilege and masking their territorial capture. Emerging in sharp relief is our focus on some of the Bangalore’s important environmental NGOs with senior administrators, scientists, and academics in tow, who anchor environmental PILs to aggressively counter the AS. Entangled in this politics are also well-meaning middle class. ‘English speaking and reading’ upper class – castes whose anxieties of ‘unsustainable development’ further misreads the AS: For them, MP representing ‘legal environmentally sustainable’ settlement constituting ‘Sakrama’ posed against the ‘Akrama’ of ‘land grab, unplanned settlements’, and ‘encroachment’.OU points towards often subtle politics: MP privileges and empowers large developers and financial institutions seeking real estate surpluses via institutional architectures that would otherwise via the AS, be redistributed to many smaller ones constituting popular society. This can explain contemporary political history of its chief ministers, across both the BJP and Congress pose contested political constituencies around mega territorialization underpinned by ‘good e-governance’ policies of digital titles, revenue management, and most recently the IT corporate backed Greater Bangalore Governance Bill. The usual academic narrative of territorial financialization of land misses the complexity of land and city politics and remains a blind spot with limited explanatory power. But also, equally misleading as an analytic, is a cartographic history that essentializes the kere as a ‘commons’ – a mythical setting of past heritage that has somehow been contaminated via uncontrolled urban growth, the lack of planning and in effect, corruption of the public sphere2.

Some extracts which give you a sense of the texture that is theorized on.

“…. Thus, when BBMP extended its territory, Rajamma went from ‘a khata’ (from the previous city municipality council or CMC) to suddenly ‘no khata’. This has hit the residents hard as having a khata or a property tax paper not only boosts ownership, but it also allows one to get loans from the formal banking system to upgrade one’s house and play the property game more effectively. However due to tremendous pressure from elected councilors to collect taxes to extend infrastructure, municipal officers used Section 108 from the 1976 Municipality Act, which allowed collection of taxes even from unauthorised constructions. Due to this bureaucratic practice, Rajamma quickly got what residents now call as B-Khata issued. However, the municipality still refuses to give a proper Khata to Rajamma and others. It is not like the Municipality does not have a policy precedent to regularise land use and plan violations and issue a Khata instead of relying on the ad-hoc micro policy of the B-khata. Way back in 1991, the first municipality AS scheme was introduced: the Karnataka Regularisation of Unauthorised Construction in Urban Areas Act to regularise plan and building by-law violations. However, in January 2017, the Supreme Court decision to initially clear the new AS in 2016, was challenged in a review due to a PIL by the civil society organisation Namma Bengaluru Foundation (NBF). As we take leave Rajamma makes a plea for regularisation as a sound financial decision: “If Akrama Sakrama opens up the BBMP will get a lot of revenue. It has expanded 8 kms circle in 2008. Imagine the properties and tax base”.

Occupancy four: From 94a to 94c to 94cc

‘..While the government is talking of clearing encroachments and recovering government lands, it has also created such forms to legalise these illegalities. We are requesting the government to stop such forms and applications.”(A senior official from Bangalore DC office quoted in New Indian express) Khanna Bosky (2022).

Even a sparrow will first build a nest. Land is a must. There is enough forest and government land to redistribute it to the poor—-Dalit Activist Sidappa

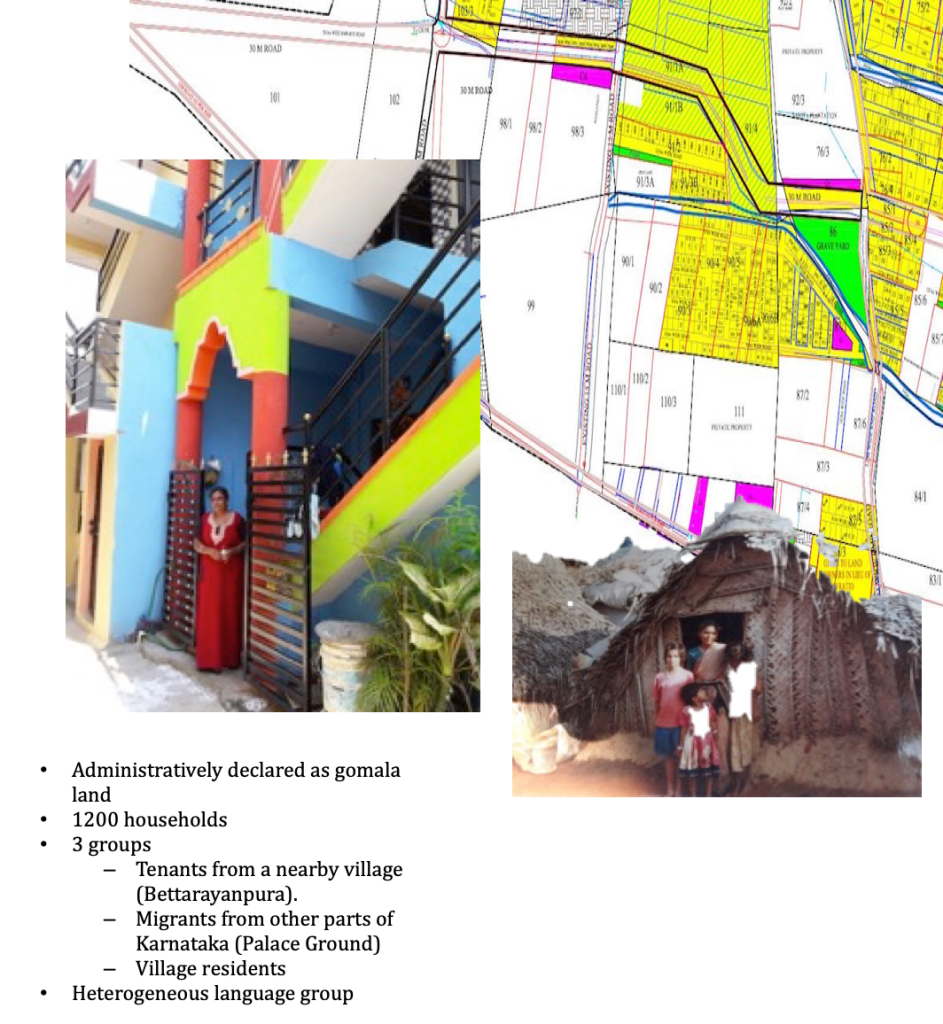

Meeting Krishna Anna, the alleged ‘slumlord’ is tough. He has been trying to control our access to the settlement on gowmala land in Northern Bangalore, and is done only after several encounters with his boys. Many residents of the rival JD (s) factions who I would later meet, go on to question his alleged political supremacy in the settlement. Anna’s office is full of local DSS (Dalit Sangharsh Samiti) and Congress party posters. He is constantly on the phone and speaking to his subordinates and I hear the name of then Deputy CM Parmeshwara (from dalit community) being thrown around a million times on ‘how the job can get done’.

Anna suddenly turns to me and starts a police interrogation: my personal details, how much I earn, my native place. I panicked a bit and started talking about how the research is about the A-S and I am not a builder. It calms him a bit and we talk about their struggles to continuously re-animate the A-S schemes of the Land Revenue department i.e. to avail hakku patra (right to deed). The hakku patras have a long history as administrative practice beginning with 94A section of Karnataka Land revenue act 1964 introduced in 1991 which regularised gowmala land occupation for cultivation purposes. In 1999 the Karnataka government, after a long period of agitation by Dalit groups state-wide, had inserted an amendment 94-c, regularising ‘encroachments’ of government land for housing purposes in rural and peri-urban areas[7].

- Water crisis spurs Royal Lakefront voters to boycott elections. No Cauvery connection for nearly two decades https://www.deccanherald.com/india/karnataka/bengaluru/bengaluru-water-crisis-royal-lakefront-housing-society-to-boycott-lok-sabha-elections-over-poor-water-supply-2974696 ↩︎

- An illustration of such a framing is given in Hita Unnikrishnan B Manjunatha Harini Nagendra (2016) Contested urban commons: mapping the transition of a lake to a sports stadium in Bangalore. International Journal of the Commons Volume: 10 Issue: 1 Page/Article: 265-293 Ubiquity Press Online access at: https://thecommonsjournal.org/articles/10.18352/ijc.616 ↩︎

Leave a comment