Following People and Electronics Through Dubai and Sharjah

Dr Nidheesh S

Three hours after landing at Sharjah airport, we booked a cab and drove toward the industrial area. The city changed quickly, the air thickened with a pale, smoky dust that clung to the metal sheets of warehouses and idling trucks. It was my first visit to the UAE. I feel as though I am strangely connected to this city. For one, I am a Malayali. And what is “Gelf”, if not a haven for fortune-seeking Malayalis. And two, like many from my coast, my father, too, had once come to this city seeking his fortune. However, I do not come seeking a fortune; I come as a researcher. I am part of an internationally funded research group, here to explore transnational urban worlds and their territorialities, and to understand how ethnicity and material flow together produce these urban geographies.

Co-researcher Dr Gayatri Rathore told Vijay and me that we were walking along a street of second-hand electronics warehouses. Inside, Urdu filled the air. We could hear snippets of instructions, jokes, and half-shouted conversations. A young man in a Pathani salwar was prising apart LED screens from computer casings with a quick, sure swing of his arm. He is paid one dirham, about twenty-five rupees, for every panel he separates. The boards he discards pile up in front of him. Two others, in faded, dusty T-shirts and trousers, watched us closely; perhaps they thought we were an inspection team.

We tried to start a conversation with them, telling them about our project and asking them if we could speak to them about their work. The warehouse manager stepped out from his cabin. He waved us in with warmth, a contradiction from his wary employees. He introduced himself as a Pakistani and offered us water and tea. He brought us to an Indian trader sharing his warehouse, whose business revolves around buying and selling LED panels. After our interview, he was eager to explain the networks he relies on, and he took us to four other warehouses around 8 PM. These warehouses were owned by Pakistanis. He introduced us to his bhais, who are not brothers by blood, but rather the suppliers who keep his panel trade moving. Very quickly, Sharjah began to immerse us in the dense and interconnected circuits of the “e-waste” trade.

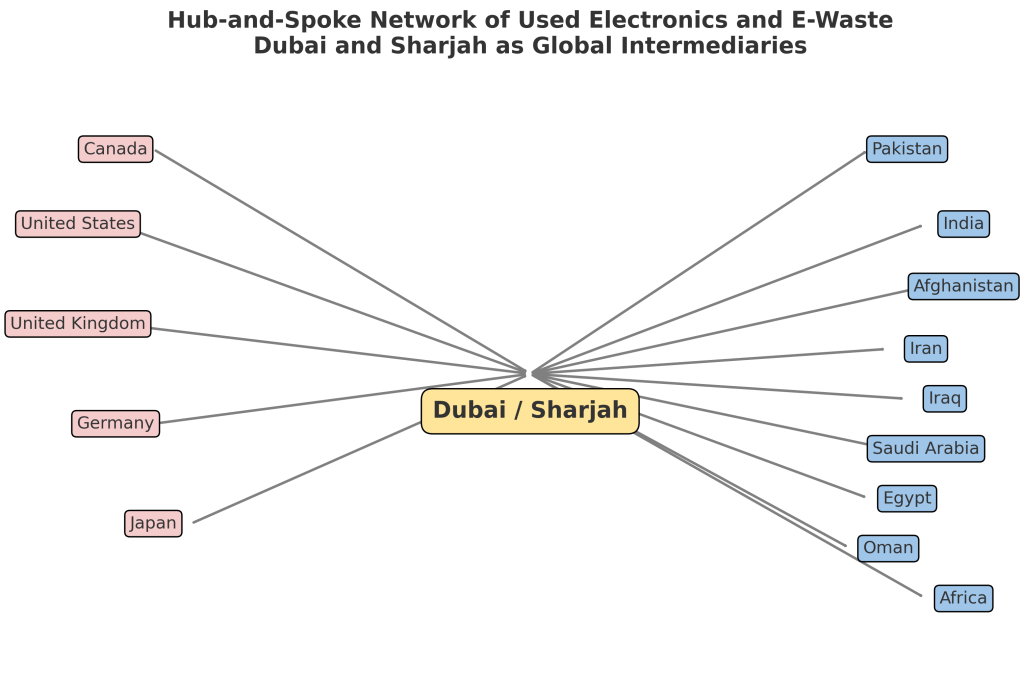

By around 10:30 PM, after six lengthy conversations and perhaps 7 to 8 cups of tea, in what everyone here refers to as Areas 2, 5, and 6, a pattern began to emerge: the devices surrounding us came from OECD countries and Japan. They were routed to Sharjah as if this location were a vast workshop or refurbishment laboratory, where the afterlife of “e-waste” begins. Around 11.30 p.m., after dinner at an Afghan restaurant near the JNP signal, I looked back on the day. Sharjah revealed itself to me not as a “periphery” or an “edge”, but as one of the global intermediaries in the second-hand electronics trade. This trade is entangled in transnational urban production that begins far from the sleek towers of Dubai.

I joined this research as a Research Associate on the ReConfigUrb project, funded by the Global Research Institute of Paris, working with Gayatri Rathore from Panthéon-Sorbonne University, Paris, and Solomon Benjamin from the Indian Institute of Technology Madras. Vijay is a refurbishing intermediary himself, based out of Bangalore, India. Our fieldwork in Dubai and Sharjah focused on following the circulation of used electronics and e-waste, mapping how these flows produce different territories and generate new connections between people and places. Rather than reading the Gulf through its familiar icons, the skyline, the freeways, the malls, we turned to the dense industrial territories, where the social and material infrastructures of transnational urbanism are made visible. These areas are not “marginal”; they are anchor points in a global circuitry, connecting North America, Europe, Japan, Africa and South Asia. Here, among stacks of dismantled computers and the quiet labour of traders, an untold city comes into view. Unlike the polished central city, these industrial territories reveal a different logic of “cityness”, one built around clusters of labour, reuse, the materiality of artefacts, and tacit knowledges that cartographic logics cannot capture.

Transnational Territorial Worlds

Sharjah’s industrial landscape spreads across nearly 9,000 acres, organised by the logic of trade. Each “Area” carries its own specialisation. Areas 2, 5 and 6 are packed with used computers, printers, monitors and their spare parts. Area 10, with its monumental scrapyards, draws early-morning collectors in search of chips, motherboards and various other components. Other vast stretches are given over to the used-car industry and its labyrinth of spares.

Inside these warehouses, the afterlives of electronics flow along a wide geography. Containers arrive from Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan and Germany. They are unpacked here, and through a cycle of repair and refurbishment, reassembled into new circuits. Most of the artefacts are shipped to Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, and other Middle Eastern markets. Many of the traders that we spoke with agreed that 80% of the electronics goods that arrive here can be repaired, and the remaining 20% can be replaced. One Pakistani trader explained it while an African dealer helped his workers pack a batch of laptops. He said, ‘These laptops came from the UK. We have a lab with 18 men here, all trained in-house. During COVID, when the world shut down, we worked night and day because demand everywhere kept rising.’

Pakistanis dominate the refurbishing trade, while Malayalis (people from India’s Kerala) handle much of Dubai’s fresh electronics network. Iranian and African buyers navigate these lanes on small electric bikes. Standing here, the scale of this network becomes clear. These industrial areas are global intermediaries that facilitate not only the movement of artefacts but also the movement of knowledge, skills and people.

Iranian Trader

One night, after a long day of fieldwork, our step counter showed nearly 20 kilometres, and we noticed a familiar face flashing past on an e-bike. I nudged Gayatri and Vijay: “Isn’t that Mohsin1, the Iranian trader we met last night?” We called out his name, and he stopped, surprised but happy to stop and greet us back, despite the late hour. Standing by the highway as trucks rumbled past, Mohsin described his involvement in the used-electronics business over the past five years, explaining, ‘I entered this through a friend. Iran is now one of the largest markets for used laptops, especially HP and Dell, popular among young Iranians. Pakistanis handle everything here; they repair, sell, and manage mid-level customs processes through their social network. They have a strong social network.’

- Name changed ↩︎

Mohsin typically spends one or two months at a time in Sharjah, managing around 400 laptops per visit. His business relies heavily on pre-orders and social media for marketing. He emphasised that, despite ongoing sanctions, “electronics have opened up new ways of trade for us.” Through traders like Mohsin, refurbished American laptops reach the Iranian youth. Their movement depends on everyday relationships and ethnic infrastructures in the electronics trade, extend urban formations beyond formal geopolitical boundaries.

Our interactions with Mohsin revealed Sharjah’s urban life, which extends far beyond the Gulf, stitching together Sharjah, Dubai, Tehran, Basra, and Karachi through flows of used electronics and repair. AbdouMaliq Simone’s “people as infrastructure” (Simone, 2004)[1] perspective is useful for exploring how these extensions are constituted through networks of trust, skills, and social and ethnic relations. In this ecology of artefacts, people and their embeddedness within the artefacts situate them as infrastructures, sustaining transnational urbanism.

[1] Simone, A. (2004). People as infrastructure: Intersecting fragments in Johannesburg. Public culture, 16(3), 407-429.

Ethnicity as Infrastructure of Mediation: Pakistanis, Malayalis, Chinese and Africans

During our fieldwork, whenever I introduced myself, Pakistani workers immediately named me “Malbari”. In the Gulf, Malabari is the popular local term for Malayalis from Kerala. What began casually as a naming act soon opened an entirely new dimension of ethnographic exploration for me. This guides my understanding of ethnicity’s role in transnational urbanism, to locate how ethnic identities clearly structure labour dynamics and territoriality within these areas.

While interviewing Pakistani migrant labourers dismantling electronic devices, a worker playfully challenged me: ‘Hey Malbari Bhai, why don’t you try what we do?‘ I accepted, joining him to separate metallic components from washing-machine motors. Soon, my designation evolved from “Malbari Bhai” to “Malbari Mazdoor” (Malayali labourer). Later, while interviewing Malayali traders in Dubai’s Naif market and Bur Dubai’s electronics districts, my “Malbari” identity became a bridge, shifting formal interviews into relaxed conversations.

Although Pakistanis predominantly control the second-hand electronics market in Sharjah’s industrial zones, there is a shared practice of refurbishing among different ethnicities. In Area 6, for instance, workers refurbishing Super General Air Conditioners explained that while Pakistanis handle repairs and repainting, a Malayali specialist exclusively manages the intricate sticker work on the units. This ethnic division of labour and its entanglements permeate the entire cycle, from sourcing goods to final refurbishment.

Many Pakistani traders described procuring electronics primarily from the UK and the US via kinship and social relations. This underlines how deeply ethnicity and social relations shape labour even in uneven geographies. Some of the traders explained that Community organisations such as the Pakistan Overseas Community (POC) play a vital role in sustaining trade. Shop owners frequently sponsor POC events to gain visibility within ethnic networks. They also maintain WhatsApp groups that facilitate the timely sharing of information about incoming shipments.

In contrast, in the electronics markets in Dubai’s Bur Dubai and Naif Market, Malayalis dominate. They also have a strong influence on the wholesale pricing of the product. A Malayali trader with 22 years of experience in the market shared the history of the Naif market with us. He owns two shops and has developed his own brand that covers a wide range of accessory products, produced and customised in China. He recalled that 20 years ago, Naif was a market mainly for groceries, with no electronic shops. His shop was among the first to start selling Nokia mobiles with multicoloured back covers. A Malayali taxi driver, who had previously worked in these electronics shops, told us that the early owners who transformed their grocery shops into electronics shops had no idea about the specifications of the products. If you go there as a customer, if the owner knows you personally, they ask the workers, ‘Hey, this man is very close to me, so give him a good computer’. Just as he would have asked them to give a friend the freshest produce from the back.

Alongside these long-established Malayali networks, new territorialities are reshaping the Naif market. One alley is now almost entirely lined with Chinese retailers selling Chinese-brand mobiles. During our visit, many of these shops were closed for the three-day Chinese New Year, but even this brief fieldwork revealed a strong Chinese presence that has grown noticeably after COVID-19. A Chinese retailer explained that their main customers are from the African continent and that phones are customised for African markets. On the pavements outside, the everyday rhythms of circulation are visible: large cartons of mobiles are sorted, sealed, and stacked for shipping. Many shipping agents have no formal offices, just a concrete slab to sit on, a messenger bag across their shoulder, and a phone in hand as they coordinate dispatches. Two such agents we met were arranging shipments to Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. To attract African buyers, non-African shop owners often employ an African shopkeeper as the familiar face of their business. These scenes extend the territorial mosaic of Dubai’s electronics markets, showing how ethnicity creates entanglements and transnational urban corridors extending Naif’s narrow alleys to African cities.

Ethnicity plays a crucial role in how communities in cities like Dubai and Sharjah develop and thrive. It helps build trust and cooperation among people, which is especially important in markets that may not always follow strict rules. By looking at these relationships, we can see that the production of cityness and transnational trade in these areas often relies more on the everyday efforts and creativity of migrant communities. These industrial sites are not passive margins; instead, they operate as active extensions, where ethnic practices and material circulation constitute urban life in ways that keep global cities moving.

Reflection

These interactions make it clear that urbanisation in Dubai and Sharjah cannot be understood solely through visible infrastructure. It emerges from the transnational circuits of artefacts, labour, and trust that bind places as far apart as California, Japan, Birmingham, Karachi, Tehran, Nigeria and Kochi. Through an ethnic lens, the city becomes a web of interconnected social relations. Pakistanis, Malayalis, Iranians, and Africans all play distinct roles, creating their own dynamic infrastructures. The “e-waste” markets and electronics bazaars in Sharjah and Dubai are, in this sense, workshops of transnational urban production, constantly reshaping what the city is and what it extends to.

As my flight back to India took off, I found myself thinking not only of the long lanes of Industrial Areas or the Naif market’s crowded alleys, but of the people who had invited me into their worlds as “Malbari Mazdoor.”

Leave a comment