Dr Nidheesh s

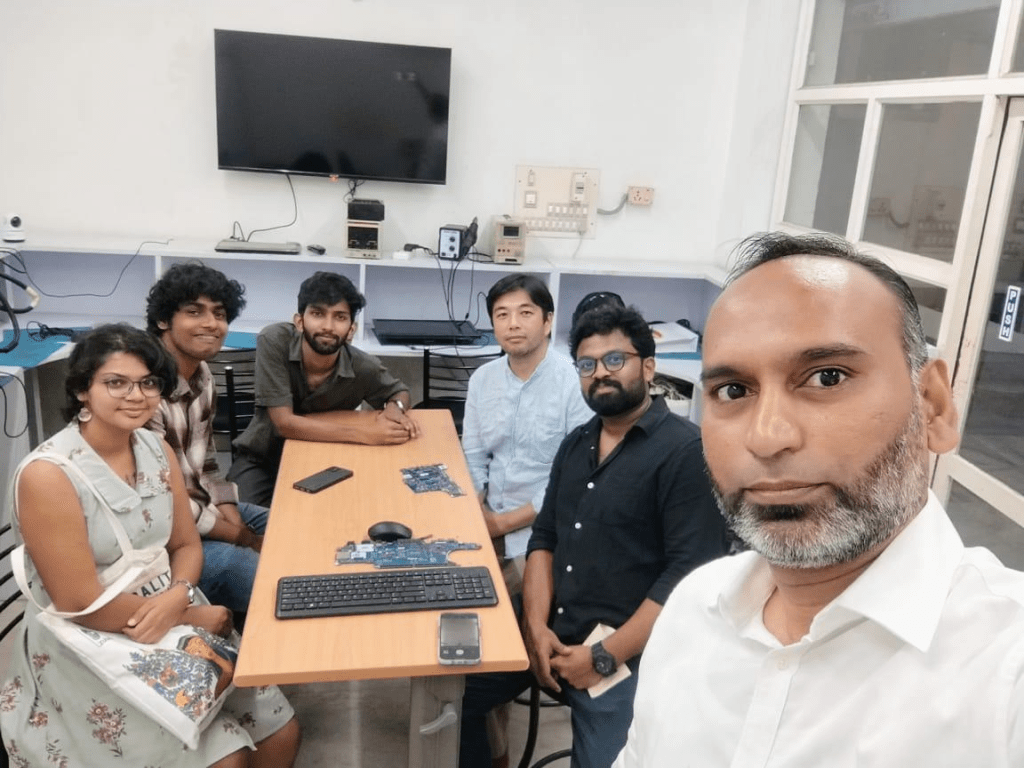

I found myself back in Ritchie Street this time, joined by three MA students from IIT Madras, Garima, Aravind, and Santhom, escorting Professor Masato Mori from Mie University, Japan. Prof Masato had come to Chennai as part of his project on e-waste, and he was interested in visiting Ritchie Street. As usual, the lanes of Ritchie Street were so crowded that even an auto-rickshaw could hardly pass. One side was stacked with parked two-wheelers, while the other side had a constant stream of bikes coming in or going out, weaving through people. The aroma of frying samosas and biriyani wafted from street vendors, adding flavour to the street.

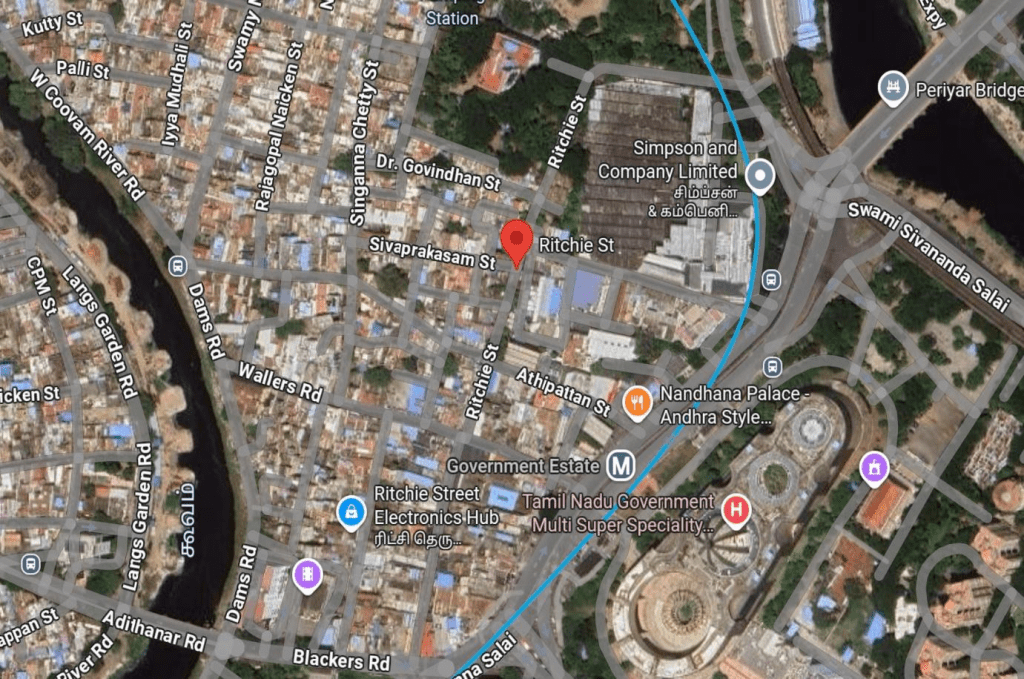

Ritchie Street sits off Mount Road, steps away from Tamil Nadu’s former secretariat (now a multi-speciality hospital), and the headquarters of The Hindu newspaper. The street we now know as Ritchie Street was once called Narasimhapuram. Drawing on the work of heritage activist and historian Sriram V, we learn that in the 1840s, a British lawyer, Arthur Macdonald Ritchie, made his home here when Madras was still under colonial rule. His son, Alexander Macdonald Ritchie, later lived on the same street, and the family house gave the place its present name.

In its early days, the area served as a market for medical supplies. Over time, it shifted to radios, transistors, and capacitors, and later to plastics. For the past thirty years, however, Ritchie Street has grown into Chennai’s hub for electronics repair. It offers repair and spare parts for computers, laptops, mobiles, sound systems, printers, projectors and whatnots. What began with just five shops has now expanded into a market of nearly 3,000 shops. Each corner hums with activity: shops stacked high with spare parts, service engineers bent over devices, and small traders locked in intense negotiations at their usual haunts. The market comes alive around 11 a.m., and by 5 p.m., as the sea breeze drifts in, the bustle gradually gives way to a lull.

Richie is a site of “intuition”, possessing trade knowledge and sensing new items that signal change, attracting traders and service engineers from all over South India. Following the pull of ethnographic intuition, we re-enter now the shops that we had not yet visited in my previous trips here. The first stop was a small mobile shop where I replaced the screen cover of my phone. Every visit revealed Ritchie Street in a new light, reshaping how we see it. For me, this visit unveiled Ritchie Street as an “ecology of knowledge” (Santos, 2014), where people themselves are the “infrastructure (Simone, 2004), sustaining repair practices, livelihoods, and urban life through their craft and connections.

Interactions in Ritchie Street

Over the three-day visit, we met many people, but among all these interactions, there are three people who stood out – three stories that show how knowledge circulates, grows, and maintains life rhythms of the market.

Moosa Games – Gaming and PlayStation Repair

The name itself is now familiar to anyone who comes here looking for gaming repairs, especially PlayStations. The shop is situated on the first floor of the Anjuman Building. Inside the shop, the shelves were stacked with consoles in different states of repair; some dissected with their skeletons on display, their circuit boards bare, and others neatly wrapped and waiting to be collected.

The owner, Moosa Bhai, greeted us with a smile. He has been running the shop for the last 15 years and has three expert engineers. The main engineer came in while Moosa Bhai was sharing his story with us. To our awe, we learned that the main engineer is entirely self-taught! His story began not with electronics but with computer games, an obsession that slowly turned into curiosity about how gaming devices worked. He shared that he moved from playing games to repairing them, eventually finding his niche in PlayStation. Now, he is mentoring two younger engineers who work in the shop: one has carved out his expertise in Nintendo devices, while the other assists with general gaming repairs.

He explained that much of his learning came from opening up older versions of consoles, comparing their internal designs, and noticing how technology changed from one generation to the next. Sometimes he consults online platforms, but mostly, it is experience, trial, error, and repetition that have made him an expert. Components, he told us, can usually be arranged through suppliers in the market, and also from discarded devices.

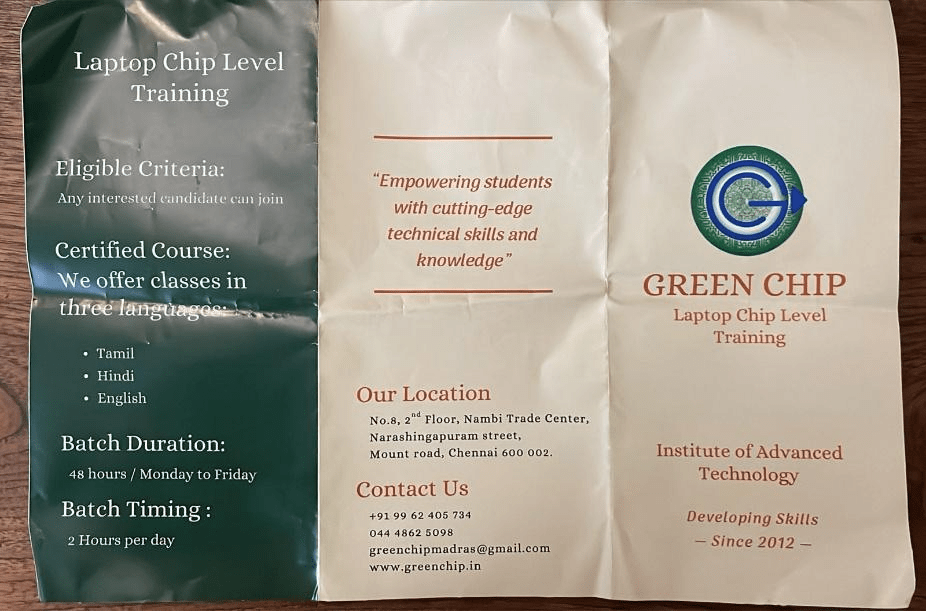

Green Chip Training Academy – Teaching Repair as a Craft

The second story is about Green Chip Academy. It is a computer training institute founded by Mr Siddhique. He was very eager to welcome us and explained the way the academy works like a seasoned teacher. For ₹25,000, he offers 48 hours of computer and laptop repair training. The hours are flexible, and students can learn according to their schedules. He has trained around 3,000 students from this academy in the last five years. Some of them now run their own repair shops. He told us that what makes his training different is not just the technical instruction but the market knowledge he shares. “Other academies don’t tell students where to get parts or how to judge the right price,” he said. “I tell them which shop to go to, whom to trust, and how to save money.”

This philosophy of openness runs deep in his teaching. He even shares chip-level repair techniques, though he admits that only about 30% of students manage to master them. He doesn’t worry about competition from former students setting up rival academies. “Knowledge should be shared,” he said with pride, “my job is to empower, and I am happy about it.”

Alongside the training, he is involved with the Infinity laptop service shop. Students can practise on real devices, including complex ones like MacBooks. The shop, the academy, and the market form an ecosystem of knowledge, each feeding into the other.

Bhai Shop – A Generational Legacy in Sound Systems

The third story belongs to Bhai Shop, one of the oldest in Ritchie Street. With its history stretching over forty years, the shop has witnessed the market transforming over the years, into its current state. Its founder, Mr Anzari, known to everyone as Bhai, was a known radio repairer in the market. Over the years, radios faded into cassette players, DVDs, Bluetooth and USB devices. With each shift, the shop found its way to adapt and carry on.

Today, Bhai’s youngest son manages the shop. He never had “formal” training in electronics but learned by watching his father work. He introduced his nephew to us, a young graduate in computer applications, who is now apprenticing under his uncle. The scene felt almost like a living archive: three generations connected by artefacts and the craftsmanship of repair.

Bhai Shop specialises in sound systems, especially retro ones. They repair DVD players, add USB and Bluetooth functions to older systems, and even service car stereos. “There is a growing crowd for retro systems,” the son explained, “people still love the sound quality.”

Bhai Shop is an intriguing site showing how knowledge is tacit and generational, constantly reshaped by changing technology. The shop, now called New City Royal World, is a reminder that repair is not only about keeping devices alive but also shows how it is connected to collective memory, inheritance, and shared identity.

Ecology of Knowledge

Walking through Ritchie Street over those three days, I kept noticing the fluidity of the knowledge and its different forms of practice. It moves with people, through conversations, gestures, practice, and even through the broken machines lying in piles on shop counters. In this market, knowledge is not abstract but experiential, pedagogical, generational and grounded. Each shop we visited revealed a different pathway into repair. Moosa’s expertise began with his own interest in games, not “formal” training, and matured through years of trial and error, opening consoles, and from discarded devices. His knowledge is experimental, improvised, and deeply personal.

At Green Chip, Siddique’s training centre, knowledge takes another shape. Here it is organised, pedagogical, shared openly, and connected to the everyday practices of the market. He does not just teach how to repair at the chip level; he also shows students where to buy parts, how to negotiate, and how to stand on their own. In Bhai Shop, knowledge flows along family lines. It began with radios, moved into DVDs, and now extends to Bluetooth speakers and car stereos. The work is not just technical; it is also about inheritance, memory, and pride. What is striking is how each generation adapts while carrying forward the legacy of the last.

As I mentioned earlier, these stories suggest an ecology of knowledge. In Ritchie Street, no single form dominates. One can see, experiential, pedagogical, apprenticeship, and improvisation coexist and interact with one another. As Donna Haraway (1988) explained, knowledge is always situated and interrelated to specific histories, practices, and bodies. Here, the situated knowledge is linked to passion, kinship, and survival, creating an ecology where various ways of knowing coexist.

The ecology of knowledge also shows that the people who work in the market function as “infrastructures” (Simone, 2004) and mediate the repair practices. With them, it becomes a web of relations where artefacts, people, and skills circulate together. This ecosystem operates in a relational way. At Moosa Games, the self-taught engineer’s knowledge does not stop with console repairing; instead, he extends this knowledge by mentoring the two young engineers. Similarly, Green Chip Academy’s Siddique adds another layer to the aspect of knowledge by sharing market knowledge, such as “which shop to go to, whom to trust, and how to save money.” In effect, the students will be empowered and exposed to the market’s existing networks of the economy. This aligns with Simone’s (2008) observation in Phnom Penh, which explained the residents’ ability to “construct the conditions that enable the city to act as a flexible resource for the effective organization of their everyday lives” (p. 186). This suggests that, in Ritchie Street, the entanglements between artefacts and people produce an ecology of knowledge, creating everyday opportunities to improvise livelihoods.

The densely packed shops, crowded alleys, and the honking of two-wheelers trying to make their way through may suggest that this ecology of knowledge is organized in a “chaotic” setting. In Simone’s opinion, these are the part of “incompleteness of the city”, its contradictions, opacity, and erratic energies are crucial for urban life (Simone, 2012). However, Ritchie Street has the presence of epistemic pluralism, where self-learning, formal training, and apprenticeship operate simultaneously, offering a form of “cognitive justice” to this ecosystem (Visvanathan, 2009).

The layers of Ritchie Street’s ecology of knowledge, ranging from people as infrastructure to its epistemic pluralism, explain improvisation as a form of “cityness” (Simone, 2010).1 This perspective also builds on Simone and Uzair’s account of Jakarta’s middle class, who navigate heterogeneous environments and improvise livelihoods (Simone & Fauzan, 2013). Ritchie Street displays a similar heterogeneity: old radios give way to PlayStations, capacitors to smartphones, with each technological shift demanding new orientations, skills, and forms of belonging. The market’s adaptive capacity is crucial for livelihood improvisations. Through Moosa Games’ experiential, Siddique’s pedagogical, and Bhai Shop’s generational craft, we see how people produce and move through knowledge practices in ways that express the cityness of Ritchie Street. To see Ritchie Street as an “ecology of knowledge” is to recognise how this ongoing churn does more than repair objects; it reproduces livelihoods, sustains aspirations, and ties Chennai into wider circuits of urban possibilities.

Every visit to Ritchie Street reveals another layer. As my friend Lalitha, a fellow PhD scholar, once wrote, Ritchie Street is a hub of “cellphone doctors,” now it is also a living archive and an open workshop of knowledge. I leave with curiosity rather than closure, looking forward to the next encounter, knowing the market will once again open up new perspectives and stories.

References

- de Sousa Santos, B. (2014). Epistemologies of the South: Justice against epistemicide. Routledge.

- Haraway, D. (1988). Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575–599. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066

- Simone, A. M. (2004). People as infrastructure: Intersecting fragments in Johannesburg. Public Culture, 16(3), 407–429.

- Simone, A. (2008). The politics of the possible: Making urban life in Phnom Penh. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 29(2), 186-204.

- Simone, A. (2010). City life from Jakarta to Dakar: movements at the crossroads. Routledge.

- Simone, A. (2012). Ghostly cracks and urban deceptions: Jakarta. In M. Mostafavi (Ed.), In the life of cities: Parallel narratives of the urban (pp. 120–133). Harvard Graduate School of Design; Lars Müller Publishers.

- Simone, A., & Fauzan, A. U. (2013). On the way to being middle class: the practices of emergence in Jakarta. City, 17(3), 279-298.

- Visvanathan, S. (2009, May). The search for cognitive justice. Seminar, 597. https://www.india-seminar.com/2009/597/597_shiv_visvanathan.htm

- According to Simone, “cityness refers to the city as a thing in the making… In other words, at the heart of city life is the capacity for its different people, spaces, activities, and things to interact in ways that exceed any attempt to regulate them. While the absence of regulation is commonly seen as a bad thing, one must first start with the understanding that no form of regulation can keep the city ‘in line’” (Simone, 2010, p. 3). ↩︎

Leave a comment